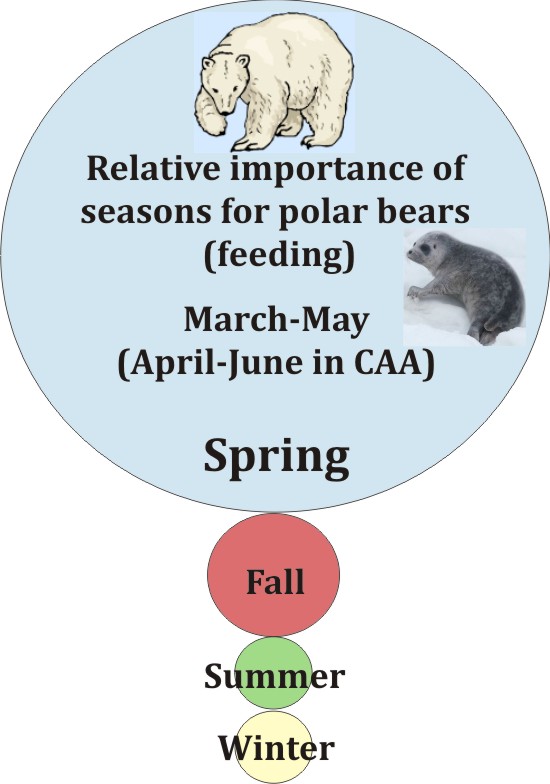

Polar bears in virtually all regions will now have finished their intensive spring feeding, which means sea ice levels are no longer an issue. A few additional seals won’t make much difference to a bear’s condition at this point.

The only seals available on the ice for polar bears to hunt in early July are predator-savvy adults and subadults but since the condition of the sea ice makes escape so much easier for the seals, most bears that continue to hunt are unsuccessful – and that’s been true since the 1970s. So much for the public hand-wringing over the loss of summer sea ice on behalf of polar bear survival!

The fact is, most ringed seals (the primary prey species of polar bears worldwide) move into open water to feed after they have completed their annual molt, which occurs by late June to mid-July for adults and subadults; newborn pups leave the ice soon after being weaned, usually by the end of May in southern regions (like Hudson Bay) and by late June in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, aka “CAA” (Kelly et al. 2010; Smith 1975, 1987; Whiteman et al. 2015).

Thus, the most abundant prey of polar bears is essentially unavailable after mid-July (and earlier than that in Hudson Bay).

Adults and subadults of the similarly-distributed but much larger (and less abundant) bearded seal tend to remain with the ice over the summer (Cameron et al. 2010:11-12) and are most likely to be available to polar bears that remain on the sea ice over the summer throughout the Arctic. Some adult harp seals (an abundant, strictly North Atlantic species) may also be available to bears on the pack ice in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait, as well in the northern sections of the Barents and Kara Seas, and northern East Greenland (Sergeant 1991).

However, research on polar bear feeding has shown that from June to October, bears are rarely successful at catching seals because broken and melting ice affords so many escape routes for the seals. Bears may stalk the seals but they often get away (see video snapshot and video below)